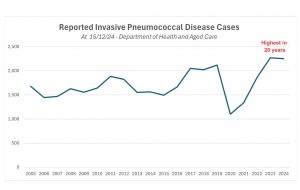

Rates of pneumococcal disease – a life-threatening bacterial infection that can attack the lungs,brain and bloodstream – have hit a 20-year high, according to national notifiable disease data. [1]

The Immunisation Foundation of Australia today revealed that more than 4,500 cases of severe pneumococcal, known as invasive pneumococcal disease, have been recorded in the last 24 months (2,269 in 2023 and 2,250 in 2024 year to date) – the highest rate of diagnoses since 2002.[1,2]

Invasive pneumococcal disease occurs when the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacterium invade sterile parts of the body and infect the lungs (causing pneumonia or empyema), brain (causingmeningitis) or bloodstream (causing septicaemia).

With a sustained surge in invasive pneumococcal disease (more than six cases per day on

average since the start of 2023), the Immunisation Foundation warns that next year may see further increase in cases with “no sign that the outbreak will ease in 2025”.

Invasive pneumococcal disease is a leading cause of death and serious illness among

children.[2 ]The infection can prove deadly within a matter of hours or days, with pneumococcal meningitis claiming the lives of one-in-twelve children with the disease. [2]

While only cases of invasive pneumococcal disease are recorded in Australia, the broader

impact of pneumococcal is significant, with non-invasive infections leading to complications

such as permanent hearing loss in children.[3,4]

“Invasive pneumococcal disease is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the impact of pneumococcal infections in Australia,” said Paediatrician and Infectious Disease Researcher Professor Peter Richmond.

“For every confirmed case of invasive pneumococcal disease, there are hundreds of noninvasive infections such as bronchitis, sinusitis and middle ear infections that we don’t record and which leave children and the elderly suffering,” he said.

Experts believe three factors may be driving the increase in invasive pneumococcal disease:

• Evolving pneumococcal strains – With more than 100 strains of streptococcus pneumoniae,the bacterium adapts over time, requiring the development of new vaccines to protect against the most prevalent and severe pneumococcal strains.[5]

• Declining vaccination rates – Childhood vaccination rates fell slightly from 93.3% in 2022 to 92.8% in 2023 in 12-month-old infants, leaving more children unprotected against invasive pneumococcal disease.[6} Alarming gaps persist among older Australians, with only 20% ofpeople aged between 71-79 years vaccinated against pneumococcal disease.[7]

• Antibiotic resistance – In more than 40% of cases, the pneumococcal bacteria that causes

invasive disease are resistant to at least one class of antibiotics.[8]

“The challenge is three-fold,” added Professor Richmond. “We’re seeing a drop in vaccine

coverage alongside emerging strains of the bacterium, and antibiotic resistance.”

“It’s important to recognise that effective pneumococcal vaccination helps prevent antibiotic

resistant infections,” [9] he said.

The Immunisation Foundation of Australia is urging the Federal Government to prioritise the rollout of newer, broader-coverage pneumococcal vaccines that have been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration and recommended by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation and Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee.

“Newer pneumococcal immunisations protect against more strains than the vaccines currentlyavailable, but a funding decision is mired in bureaucratic red tape,” said Catherine Hughes AM, Founder and Director of Immunisation Foundation of Australia.

“New generation vaccines need to be rolled out through the National Immunisation Program without further delay. We simply can’t risk not having the best available pneumococcal protection.”

“Invasive pneumococcal disease can cause permanent disability and even death. We have thetools to make a difference, and now is the time to ensure Australians at greatest risk of infection are protected,” Ms Hughes said.

The Foundation’s new Prioritise Pneumococcal Protection campaign aims to heighten awareness of pneumococcal disease and advocate for nationwide access to the best available pneumococcal protection.

References

1. Australian Government Department of Health, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS).

Number of notifications pneumococcal disease by year, age group and sex.

2. CDC. Pneumococcal Disease Symptoms and Complications. 2024. Available at:

www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/signs-symptoms/index.html

3. Public Health Laboratory Network. Invasive pneumococcal disease (Streptococcus pneumoniae) Laboratory

case definition. 2022. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/06/invasivepneumococcal-disease-laboratory-case-definition_0.pdf

4. Leach, AJ et al. Hearing loss in Australian First Nations children at 6-monthly assessments from age 12 to 36

months: Secondary outcomes from randomised controlled trials of novel pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

schedules. PLoS Medicine. 2024 Jun 3 [cited 2024 Aug 17];21(6):e1004375–5. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38829821/

5. Raguindin PF. The changing epidemiology of pneumococcal diseases: new challenges after widespread routine

immunization. International Journal of Public Health. 2020 Jun 12;65(6):709–10.

6. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Australia. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report

2023.

7. Prioritising prevention: Addressing the burden of pneumococcal disease in Australia. Evohealth, 2024.

8. CDC. Pneumococcal Disease Surveillance and Trends. 2024 Available at:

www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/php/surveillance/index.html

9. CDC. Antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. 2024 Available at: www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/php/drug