Researchers have gained insight into how a toxic protein, known to trigger muscular dystrophy, could be ‘switched off’ – a pre-clinical discovery that could spearhead a treatment for the debilitating disease.

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a progressive, muscle-weakening condition characterised by the death of muscle cells and tissue. It is currently incurable and untreatable.

The discovery, from a global research collaboration led by WEHI, found a gene linked to FSHD can be safely boosted in the lab to potentially disable the toxic protein, bringing the team closer to finding a future treatment for the genetic condition.

- Findings show it is possible to boost the function of a gene linked to a muscle weakening disease known as FSHD, using pre-clinical models of the disease.

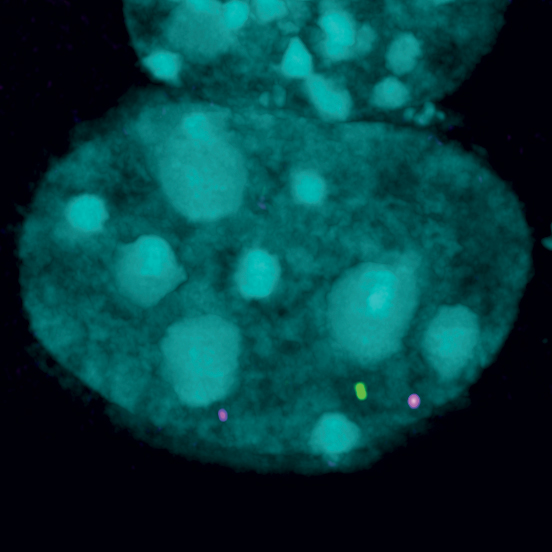

- People with FSHD have reduced levels of a ‘silencing’ gene, known as SMCHD1. Researchers found boosting SMCHD1 function could limit the production of a toxic protein known to trigger deterioration of healthy muscles.

- The research rewrites our understanding of how SMCHD1 switches off the toxic protein, clarifying how the gene’s ‘silencing’ capabilities could be boosted to find a future treatment for the condition.

FSHD affects around 870,000 people worldwide, including more than 1000 Australians.

The inherited disease is caused by the production of a toxic protein that cannot be effectively ‘switched off’. SMCHD1, a gene discovered by WEHI researchers in 2008, is critical for switching off the production of this toxic protein.

WEHI’s Professor Marnie Blewitt leads the only drug discovery effort in the world that leverages in-depth understanding of SMCHD1 to design novel therapies to treat degenerative disorders like FSHD.

Prof Marnie Blewitt, Acting Deputy Director and Laboratory Head at WEHI, said it was invaluable to know the gene can be safely boosted in the lab, after years of research flagging this possibility.

“While most people with FSHD have a normal life expectancy, their quality of life is significantly decreased due to the challenges they experience because of the serious muscle weakness brought on by this disease. We want to improve their health and quality of life,” she said.

“The less SMCHD1 people have, the worse the disease symptoms.

“That’s because SMCHD1 normally silences the expression of the protein known to destroy muscle function in FSHD. When this process malfunctions, it causes this toxic protein to be produced in excess, impacting healthy muscles.

“This is why our team has dedicated years to finding ways to boost SMCHD1 function, in hopes of restricting the production of this toxic protein and protecting muscle function.”

In a collaboration with Leiden University Medical Centre (Netherlands), the team found that in pre-clinical models of disease, boosting of SMCHD1 function limited the production of the toxic protein, with no adverse side-effects.

“The next step is to figure out how to translate these milestone findings to benefit humans, by determining the best way to boost SMCHD1 and its silencing powers to hopefully find a cure for FSHD.”